Matte Painting – Big Picture

This post is also available in: 简体中文 (Chinese Simplified) 繁體中文 (Chinese Traditional)

Matte World Digital © 2002

“It was always effective, when you went to the big films in those days, that people actually were so moved by the impact of these tremendous big screen cataclysms and effects… But the secrets [of their creation] were well kept.”

Jesse Lasky, Jr., screenwriter, The Ten Commandments

The decade of the 1950s could be called the Big Picture era. “Wide-screen” debuted in 1952 with Cinerama, which utilized three cameras for filming, three electronically synchronized projectors running at twenty-four frames per second, and a gigantic curved screen, creating a feeling of limitless space. In 1953, Twentieth Century Fox ushered in CinemaScope, and a host of other big-screen innovations followed from the various studios.

The term Big Picture also sums up the type of production then in vogue. While the movies had always been enamored of epics, wide-screen technology provided an irresistible staging ground for blockbuster productions and the matte paintings needed to bring those grand visions to life.

The Great Race (1965)

The Great Race is a madcap chase movie and a particularly complex production, given its period setting at the turn of the twentieth century and its premise of an around-the-world race between rival automobile companies. This production was another challenge for Linwood G. Dunn’s Film Effects of Hollywood, with matte artists Albert Simpson and Cliff Silsby creating more than twenty-five matte paintings for the show. The Great Race also marked a reunion for Simpson and Dunn, both of them veterans of RKO’s glory days and such productions as The Devil and Daniel Webster.

The effect seen here is a classic “jeopardy shot,” successfully and safely created by combining Albert Simpson’s matte-painted building with live action of this performer hanging from a ledge set that was, in reality, only a few feet off a soundstage floor.

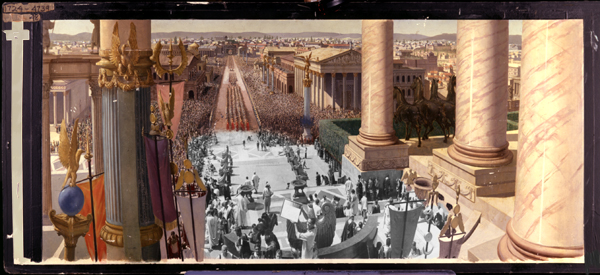

Ben-Hur (1959)

Lew Wallace’s story of Judah Ben-Hur, set in the time of ancient Rome, was first adapted for the screen in 1927. The early film was legendary for its sea battle and chariot race when this remake went into production. But audiences were ready for an updated version, and the new blockbuster swept the Oscars with an astounding eleven golden statuettes, including Best Picture, Best Actor (Charles Heston in the title role), and Best Visual Effects.

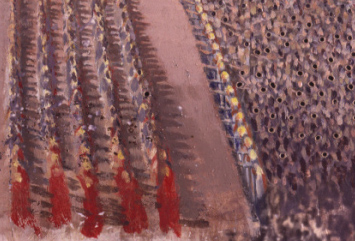

Matte paintings were vital in re-creating the grandeur of the lost world in Ben-Hur. For this image of the emperor and an enthusiastic crowd greeting legions of soldiers returning from another victorious campaign, MGM matte painter Matthew Yuricich not only painted Rome in all its imperial splendor, but added that old matte painter’s trick dabs of paint to represent people, from “marching” soldiers to waving crowds. Yuricich didn’t use a glass but Masonite board; he then poked holes behind the painted people and, by moving another painting behind the holes, created a flickering effect and the illusion of movement.

In the “before” image we see the painting as Yuricich worked on it, complete with a black-and-white photograph taken on the small live-action set and pasted onto his Masonite. Painting to a photographic reference helped MGM matte painters to line up their paintings perfectly with live-action sets. This finished painting was then combined with the live-action element in the optical printer, the live film simply replacing the photographic reference.

Yuricich explained that his creative partner Clarence Slifer (who had moved to MGM in the last days of Selznick International) used an optical printer to replicate photography of a group of live-action soldiers, rephotographing the same element in smaller perspective to create the image of columns of soldiers marching in review. But on the first optical composite test combining the new dupe negative of a legion of soldiers with the matte painting, things got a little out of whack, Yuricich recalled: “The foremost legions were to reach the base of the steps [of the emperor’s reviewing stand], turn screen right and exit frame. Unfortunately, because our timing was off, the entire legion turned at once, marched under the matte line and disappeared! We had a good laugh seeing that. By take two we had it figured right.”

It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963)

Director Stanley Kramer’s all-star comedy with a cast ranging from Spencer Tracy and Milton Berle to Jonathan Winters and Phil Silvers, plus a Three Stooges cameo thrown in for good measure is a madcap dash for buried cash. In this penultimate scene, the Mad gang are trying to get off the collapsing fire escape of a dilapidated building, but have tumbled onto a fire engine ladder that becomes overweighted and starts swaying dangerously back and forth.

“What we were doing here was trying to make things look real and scary,” explained Linwood G. Dunn, who created this effect with matte artist Cliff Silsby at Film Effects of Hollywood, the independent company Dunn formed after RKO closed in the 1950s. “Our matte-painted building completes a fictitious twelve-story building that had, as its base, a two-story set shot on location. It was our job to make this sequence look convincing, and who’s going to know it’s painted if it’s a good job? That’s the matte painter’s job on a shot like this to be invisible.”

Dunn, ever the innovator, years later noted this shot was an example of what would become known in the digital age as “previsualization,” the rough computer graphics imagery that works out the look of a shot or effects element. Dunn’s version was a crude test of a swaying, three-foot miniature fire ladder, which became a running joke between Dunn and Kramer, the director harboring a worried suspicion that the rough test was going to be as good as it got.

This Mad shot was also part of a traveling presentation in which Dunn revealed secrets of visual effects, in the process inspiring many a young person to enter the business, including Syd Dutton, a future matte painter and cofounder of Illusion Arts.