Matte Painting – Way of the Artist

Matte World Digital © 2002

“Al Whitlock taught me things mostly by osmosis. It was about being around him, seeing him. Al didn’t believe in drawing out a shot. It was about the energy of the moment when he was painting. He believed you had to come to a matte painting with focus and a certain energy.”

Syd Dutton, Whitlock protégé and cofounder, Illusion Arts

As film production began changing with the digital breakthroughs of the 1990s, it became necessary to make a distinction between digital and “traditional” effects. While computer graphics entailed complex new digital technology, traditional effects artists worked in a hands-on world with hallowed tools of the trade, traditions, and techniques passed down the lineage of their craft.

Although Albert Whitlock always worked in the traditional era, he stands in the first rank of the pantheon of matte painters, be they traditional or digital artists. Like others from those predigital days, he could wield his brush expertly, each stroke leaving impressionistic dabs of paint that “read” as real when a final painting was filmed. But Whitlock was also a master at designing and enhancing his paintings with special effects, optical illusions, and effects photography. During his reign as head of the Universal matte department he won two Academy Awards, became the trusted effects guru for Alfred Hitchcock, and was in demand by such directors as John Huston, Robert Wise, and Hal Ashby.

Mame (1974)

This film about a wealthy eccentric (played by Lucille Ball) whose adventures span the flapper era of the Roaring Twenties, the stock market crash, and the Depression, featured this fantasy scene, created by Albert Whitlock, in which Mame and her young ward Patrick (Kirby Furlong) sit on the most precarious of perches. The stage setup needed only one practical spike of the Statue of Liberty’s crown, and the painted blue floor was not a “bluescreen” effect but a guide for the ocean that would be part of Whitlock’s final painting.

Although the shot seems impossible, Whitlock actually designed the scene as it could potentially have been filmed, he revealed: “I don’t like the omnipotent viewpoint, those kinds of shots never feel real to me. So I designed it to look as if the camera had been set up on the torch of the statue’s raised arm. I think taking a realistic approach to how you could really shoot something like this helps make the shot seem more real. Of course, they would never let you shoot it like that for real, and the actors would refuse, anyway. I remember that although the little boy had a safety belt on him, he was nervous at first, but got more comfortable after the first take.”

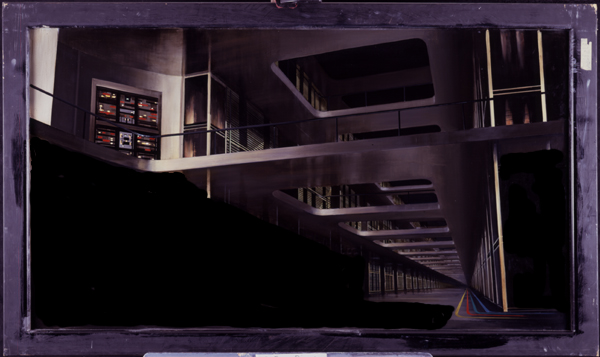

Colossus: The Forbin Project (1969)

This film, released by Universal the year men first walked on the moon, still seemed like science fiction in a world in which personal computers didn’t exist. But big mainframes, kept in the province of scientists and academics, did exist as did fears that those mysterious machines might someday supplant humans. That fear fuels this film’s premise, with Dr. Forbin working in a mountain fortress research center where he has developed Colossus, a thinking machine that decides human beings are The Enemy.

In this ominous shot, crafted by Albert Whitlock, Dr. Forbin turns on the seemingly endless computer banks that comprise Colossus. Whitlock was always an advocate for an original-negative approach, trying to get a shot “in-camera” and thus avoid the inevitable degradation of a filmed image that is rephotographed many times in the optical duping process. Here, Whitlock utilized painted cel animation overlays of silver light panels to create the illusion of his computer turning on in stages. The effect was captured on the original negative, with the camera rewound several times for each new exposure.

The shot also had to match the practical lighting effect for the live action element of Dr. Forbin walking down the vast computer corridor. “I thought we’d get lucky and smoothly match my animation in the painting to the on-set lighting,” Whitlock recalled. “What helped was Forbin standing exactly between the lighting effect, near the matte line so you didn’t notice the changeover. And he’s wearing a white suit that distracts your eye just at the right time. I remember this shot went over very big with the brass in the front office. They loved the way the lights turned on.”