Matte Painting – Dream Factories

This post is also available in: 简体中文 (Chinese Simplified) 繁體中文 (Chinese Traditional)

Matte World Digital © 2002

Forgive me if I say that one of the many fields in which the Selznick International pictures were way ahead of the rest of the business was in their enormous use of matte shots, optical effects.

When Gone With the Wind came along, it became even more apparent to me that I could not even hope to put the picture on the screen properly without an even more extensive use of special effects than had ever before been attempted in the business.

David O. Selnick, producer; 1956 letter to William Paley, CBS

By the time of Hollywood’s “Golden Age” in the 1930s and 1940s, the arc of movie history had intersected with all the roads that various pioneers had been building into the creative frontier: The movies had sound, color, increasingly sophisticated optical and special effects, and a narrative drive that ranged from the epic grandeur of Gone With the Wind to the romance and dramatic intrigues of Casablanca.

The hallmark of this era was the rise of the “dream factories,” major Hollywood studios that controlled the entire process from script development and production on studio backlots and soundstages to marketing and distribution in studio-owned theatrical chains. Even high-profile independents, like Selznick International, were organized to create films in-house.

Key components in the studio system were the special effects and matte-painting departments that had become indispensable to realizing the grand illusions increasingly sophisticated audiences desired.

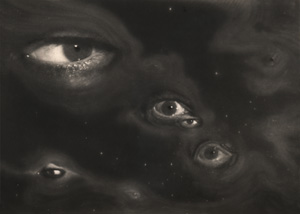

Spellbound (1945)

This psychological thriller, the second film director Alfred Hitchcock made under the banner of Selznick International, was steeped in Freudian symbols and the mysteries of psychoanalysis. In the story, Ingrid Bergman plays Dr. Constance Petersen, who works at Green Manors, a mental hospital in Vermont. She falls in love with an amnesiac, played by Gregory Peck, joining him on a journey to discover the dark secret of his forgotten past. (A poster for the film used the slogan, “The Maddest Love that ever possessed a woman.”)

Despite its dated take on the labyrinth of the mind, Spellbound remains celebrated for the dream sequence designed by surrealist artist Salvador Dal, which visualizes a psychoanalytic journey into the subconscious of Peck’s troubled character. Author Ken Mogg, in The Alfred Hitchcock Story, calls the Dal -designed dream the “heart of Spellbound.”

Although the dream in the final film is but a reflection of the hallucinatory sequence Hitchcock and Dal originally imagined, it is still full of powerful imagery, including the disturbing elements of these floating eyes for a hallucinatory fly-through that also combines Dal matte paintings of eyelashes and stars and a stage set that incorporates a Dal – painted backing.

Selznick studio effects cameraman Clarence Slifer, who composited the entire sequence on an optical printer, recounts the way he photographed the eye elements: “Hitchcock wanted some bloodshot eyeballs moving through the scene. I went down to Skid Row [in Los Angeles] on Christmas Eve to photograph these bleary-eyed fellows who’d been drinking heavily all their lives. We got more varieties of eyes than you can imagine, from bloodshot to weepy and then expressionless eyes. They looked frightening, just staring. It was very creepy. Then [on the optical printer] we’d reduce them down or enlarge them, we’d put one man’s eyes into the pupil of another man’s eyes, and then composite them together with matte paintings. In the final, the eyes just look at the audience as we fly through them.”

Citizen Kane (1941)

Citizen Kane remains the measure by which all films are judged, a production that broke all the rules and made up some new ones. Producer/director Orson Welles was barely in his mid-twenties and fresh from scaring the radio audience of his Mercury Theater on the Air with his infamous production of “The War of the Worlds” (the H. G. Wells thriller of a Martian invasion reenacted as a series of live news bulletins) when he answered the call of Hollywood.

RKO studio gave Welles total control and a blank checkbook with which to realize his vision. And although the mercurial genius would never again enjoy such creative freedom under the aegis of a major studio, Welles seized the day and produced arguably the greatest movie ever made. The genius of Citizen Kane pervades every frame, and the sum total of it has been famously chronicled: the Oscar-winning screenplay by Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz, the ensemble cast (with Welles himself starring as media mogul Charles Foster Kane), the breakthrough cinematography of Gregg Toland, and Bernard Hermann’s powerful score.

But overlooked in this litany is that the production’s creative freedom allowed for the advancement of the optical printer, a rephotographing device for creating complex composites including matte-painting shots. The art of matte painting was integral to the film’s success. The famous opening tracking shot into the bedroom window of Kane’s stately Xanadu, where the great man lies dying, was created as a succession of matte paintings, each optically dissolving into the next; the establishing shots of Xanadu itself were photography of matte paintings throughout this sequence and the movie itself.

The image displayed here shows Xanadu under creation, a scene from the “News on the March” newsreel segment that triumphantly details the life of the recently deceased Kane. This Mario Larrinaga painting of Kane’s mansion was combined on the original negative with a matte of a tabletop miniature construction set, complete with stop-motion animated trucks and earth movers. RKO special effects department head Vernon Walker had that background footage rear-projected with a live-action foreground of the worker and construction rigging.

Linwood G. Dunn, RKO’s guru of optical printing, added a final touch to this early example of media manipulation. “My department had the reputation of being unsung heroes, because when you fixed up a problem shot and it looked good, nobody knew you’d done anything to it,” Linn noted. “We did a lot of that on Kane, but on this shot Welles wanted it to look duped, like it was old, grainy, scratched-up stock footage. So I purposely duped it over and over, so it’d look bad.”