Matte Painting – Wonderful Magic

This post is also available in: 简体中文 (Chinese Simplified) 繁體中文 (Chinese Traditional)

Matte World Digital © 2002

For a long time [in the post-studio era] Hollywood seemed to forget the wonderful magic that you can create, like the scenes we did in Alexander Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad…. Alex Korda would come down and say, ‘Mickey, I think you should stop shooting the ship in the storm and come up to the studio. We’re going to shoot the scene of the flying horse.’ This was so wonderful to be a part of, especially for somebody who has been in pictures as long as I have. Effects work is meat and drink to me and should be to every filmmaker.

Michael Powell, director

Effects-filled fantasy films hail from the dawn of movies and the glass-walled studio outside Paris where stage magician Georges Méliès produced cinema’s first fantastic visions. As the technology of movies evolved from silent films to “talkies,” from black and white to Technicolor, as devices such as the optical printer became more sophisticated, so too did the possibilities of creating fantastic effects.

But throughout much of movie history, matte painting has been the undisputed master craft for creating what director Michael Powell has called “wonderful magic.”

The Thief of Bagdad (1940)

Films such as The Wizard of Oz are hailed as highlights of Hollywood’s Golden Age, but in that era movies were golden everywhere, particularly at the London studio of producer Alexander Korda. For Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad, another breakthrough Technicolor fantasy, the creative team included codirector Michael Powell, a man who gloried in the creative possibilities of visual effects, and matte painter Percy “Pop” Day, who was indispensable to producing the visions for this and other Korda productions.

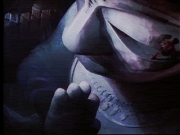

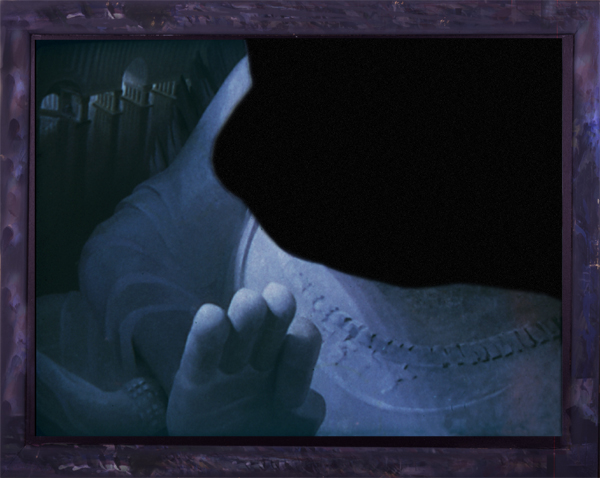

Here we see Abu (played by Sabu), the slickest street thief in all Bagdad, stealing into the mystical Temple of Dawn to pluck the “All-Seeing Eye” ruby from the statue of a mythical idol. Once again, only a sliver of live-action set is needed to create a scene that would be too costly to build, with Percy Day’s brush underscoring the jeopardy of the situation through the statue’s tremendous scale and dramatic composition.

This image began with production designer Vincent Korda supplying Day with a rough sketch and Day improving on the design during the actual matte painting. Future matte-painting great Peter Ellenshaw, Day’s stepson and his assistant on Thief, recalled the work on this shot: “Pop would say, ‘I think we should make the idol’s hand bigger so you can see it, it should go here,’ and so on. This is one of Pop Day’s extraordinarily simple compositions. He taught me that the audience has three seconds to see the matte shot, and if it doesn’t make any sense, it’s a miss!”

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

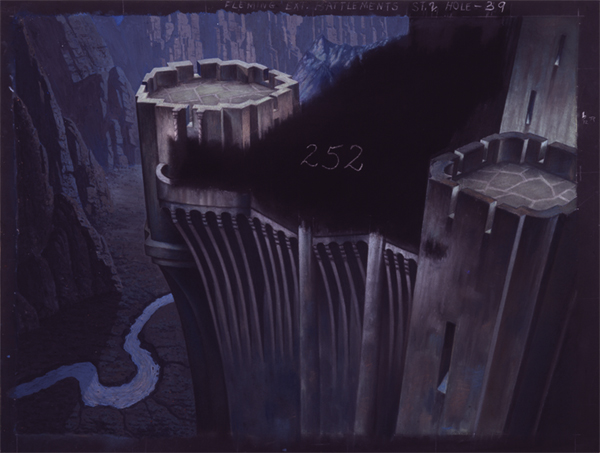

Dorothy’s adventures in the magical land of Oz had previously been celebrated on stage and in the movies, but the 1939 MGM production remains the definitive version of author L. Frank Baum’s classic story. Warren Newcombe’s matte painting department at MGM was kept busy on Oz, producing pastel-on-board paintings that ranged from the bleak landscape of Kansas to the Technicolor wonders of Munchkinland and the Emerald City as well as this view of the Wicked Witch’s Castle.

This image, with painting and live action filmed by MGM effects camera ace Mark Davis, illustrates a major advantage of using matte paintings, the creation of an entire environment. The matte painting also reveals the sublime qualities that go into telling a story with pictures: The down-angle composition dramatically emphasizes the peril of Dorothy and her friends trapped in the witch’s lair, while the painting’s slightly fantastical quality (including animated twinkle effects added to the distant river), convey the storybook-illustration look the production desired.