The-Invisible-art-Matte-Painting-Pioneers

This post is also available in: 简体中文 (Chinese Simplified) 繁體中文 (Chinese Traditional)

Matte World Digital © 2002

I have some amazing memories to tell you about a time and place now lost in the dark shadows of the past.

Norman Dawn

Trailblazers set a course into uncharted frontier, map unknown terrain, make the rules, and lay the foundations that those to follow will build. For the pioneers of movie matte painting, everything was a revelation, and happy accidents could become important techniques.

For artists like Norman Dawn, one of the pioneers of those seminal days of filmmaking, a whole creative world opened up with the technique of the “glass shot.” By putting a glass canvas on an easel at some outdoor location and adding a painted element to the landscape and performers visible through the glass, the artist could then look through the camera eye and see a whole image plucked out of the imagination.

The rigors and limits of the glass shot the images had to be painted at the location and shot at the exact time of day when sunlight and shadows matched painting and live action led to the next major advance, the use of double exposures and matte “effects” to combine separately filmed elements on the same roll of film (also called the “original negative”).

The Great Train Robbery (1903)

One of the pioneering works of film, Edwin S. Porter‘s The Great Train Robbery marked many firsts: it was the first feature (albeit a modest twelve minutes long), had the first semblance of narrative, and even included the first “shock” ending, as one of the train robbers points and fires his gun at the viewer.

Most important for the art of illusion, Porter’s film has arguably the first sophisticated effects shot, a matte effect that used two separate exposures on the same strip of film to provide the illusion of this passing train seen outside the telegraph window. It was a deceptively simple technique, but full of portent: A black backing blocked out the window on a live set of the telegraph office; the set was filmed, that film was then rewound, and a black matte box on the camera was used to cover the part of frame already filmed, allowing footage of a passing train to be exposed into the window area.

Pioneers like Norman Dawn took note of Porter’s innovation. Dawn also observed a slightly shaky quality between the two separate exposures. More sophisticated cameras to come would allow for composites that avoided the dreaded “weaving” that could betray the effect when an artist was attempting to fit multiple exposures of film into one seamless image.

Porter’s Great Train Robbery matte shot, whatever its technical failings, was still a masterful illusion, a huge leap in the art of creating sophisticated images. Unlike modern audiences literally raised on moving pictures, those first moviegoers were eager and willing for whatever wonders filmmakers could create. As Karl Brown, assistant cameraman for director D. W. Griffith, once wrote: “If the pictures moved, that satisfied [audiences]. And if the pictures showed things that were wondrous to behold, all the better.”

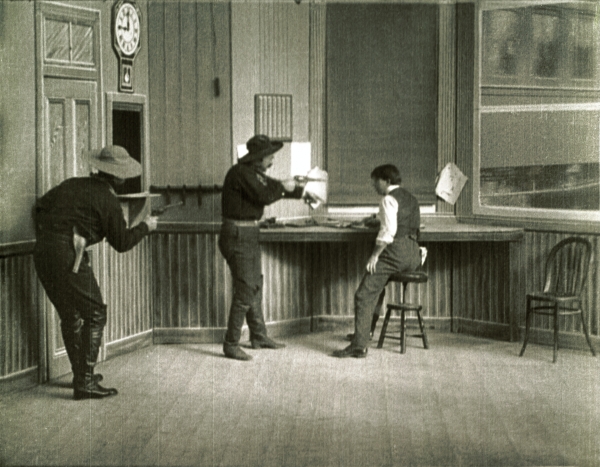

Noah’s Ark (1929)

Movies quickly became vehicles for telling stories, and some ambitious filmmakers were even convinced they could deliver visions of salvation for humanity. Noah’s Ark, directed by Michael Curtiz (who would go on to direct such classics as Casablanca), is an example of an inspirational epic, with a parallel story that contrasted a message of duty and patriotism set during World War I with a flashback story line to the biblical days of Noah, complete with a dramatic re-creation of the legendary flood that drowns a wicked world.

In this behind-the-scenes view, two Noah’s Ark crew members prepare a classic glass shot, lining up the live set and artist Paul Grimm‘s glass canvas of the pagan city of Akkad. (This angle, as photographed by effects artist Bud Thackery, is different from the final painting and live-action composite seen here.)

Thackery recalled the glass shot work for Noah’s Ark: “I helped set up these big six-by-eight-foot glasses in wooden frames bound in rubber so they wouldn’t crack as the sun hit them later in the day. I’d lay in the vanishing points on the glass by looking through the camera and then paint out the perspective lines on the glass. I’d go as far as I could with the base colors, getting it ready for Paul Grimm. I’d do the photography when he was finished with the painting. We’d have to be ready to shoot at a specific time, like two-fifteen in the afternoon, so the sun’s angles would be the same on the set as on the painting. If the sun didn’t come out, we’d have to wait to shoot until the next day.”