Matte Painting – The Force

“What’s great about matte painting is you get to control a little bit of the movie. Sure, you’ve got everybody telling you how to do it, but you get to bring across some narration, maybe even an emotion, and that’s heady stuff. It’s your moment. It can be intoxicating, can make you feel powerful. You’re fighting for control over this image!”

Harrison Ellenshaw, Disney Studio/Industrial Light + Magic matte painter

In 1975 a young director named Steven Spielberg saw his movie Jaws become a national phenomenon, while another young director named George Lucas was in production on a little film called Star Wars. This would be the beginning of a new era, with genres resurrected from science fiction themes to adventures patterned after old Saturday matinee serials and pumped up into effects-fueled spectacles with crossover appeal and boffo box office. Although Lucas had always imagined Star Wars as a saga requiring a number of films, in the decades to come any successful movie might produce potential sequels. Marketing would become more sophisticated, with the phrase “summer movie” understood to mean a potential blockbuster. And with the billions that Star Wars licensed products have generated (the rights to which George Lucas shrewdly kept during his first Star Wars negotiation with Twentieth Century Fox), once marginal, ancillary marketing tie-ins became potentially more lucrative than the box office itself.

The new blockbuster era was also a time of transition. Lucas’ Industrial Light + Magic (ILM) effects house, organized to create the effects for Star Wars, was soon being hired out for effects assignments at other studios, and other independent effects houses such as Apogee and Boss Films entered the field. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the think tanks within ILM and other effects shops were busily making the first feature films to venture into the digital realm.

With fantasy and adventure themes so popular, matte painting was more important than ever. Thus, in a time of change the tradition continued, with brush and oils truly conjuring worlds.

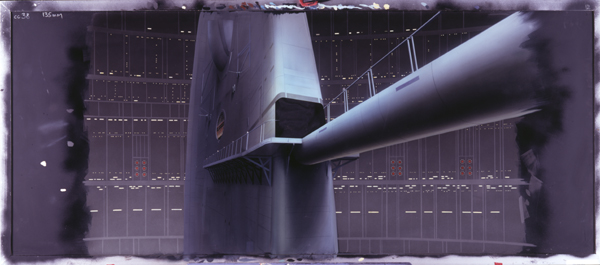

Many Star Wars fans find this sequel to the phenomenally popular first film their favorite chapter, with dramatic plot turns including Luke Skywalker’s first encounter and apprenticeship with Jedi master Yoda and the dramatic final confrontation between the aspiring Jedi Knight and the evil Darth Vader. The fantastic ILM effects ranged from the stop-motion animation of the Imperial Walkers during their attack on the Rebel base on ice planet Hoth to matte paintings creating everything from an asteroid field in space, to the swamp planet of Dagobah and entrancing visions of Cloud City.

Here we see a shot from the dramatic duel between Luke and Vader in an air shaft on Cloud City. ILM’s matte department composited the live action of the doorway and actors with a Ralph McQuarrie matte painting, via a “front-projection system” developed for Empire by Richard Edlund and Neil Krepela. The light-saber beams themselves were rotoscoped animation elements provided by ILM’s animation department, which Krepela’s matte-camera assistant Craig Barron, who was working on his first movie, composited into the scene using the front-projection system.

For McQuarrie, who had developed the look of Star Wars back when Lucas was first dreaming everything up, Empire was a chance not only to create production designs of characters and environments, but to follow through and bring them to life as final matte-painted shots. McQuarrie laughed as he recalled that the exact nature of the environment pictured here was never totally explained before his department set to work: “I never quite figured it out, frankly. That’s one of the things that was total fantasy. I’ve forgotten whether it was my idea, or George’s, or somebody else’s to use an air shaft. Basically, the point was George wanted a cliffhanger location for the duel.”

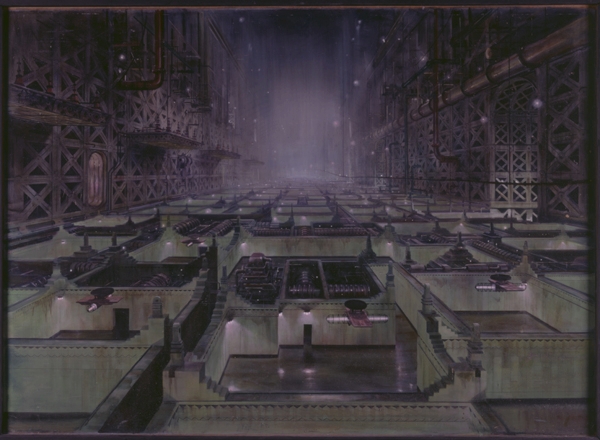

In this David Lynch production of the Frank Herbert novel, the planet Arrakis is a desert world in which water is more precious than gold and Melange the “spice” vital for interstellar travel is mined. Against this backdrop a Holy War is brewing, as the people long for a messiah to lead them against the evil Harkonnen empire.

Dune, released by Universal, was another challenge for Albert Whitlock’s matte department. Whitlock gave his apprentice Syd Dutton (who would cofound Illusion Arts with Universal matte cameraman Bill Taylor) complete freedom to create this shot of a cable car passing over the labyrinthine city of Giedi Prime, the domain of Baron Harkonnen and a center of spice processing. This shot followed the Whitlock philosophy of shooting matte paintings onto original negative.

Dutton’s work was inspired by a sketch provided by Dune production designer Tony Masters. It was also a unique effect on the production, as Bill Taylor described in an article documenting the making of the film for the April 1985 issue of Cinefex: “The Giedi Prime shot was unusual for several reasons…. First, because there was no set involved at all. The set had long been struck by the time we got the assignment. So it’s a full painting, with just a couple of live-action inserts. Second, the painting was actually begun before the live-action elements were shot. Third, it also marked the first time we photographed our own motion-control miniature the cable car for incorporation into a matte shot.”

One of Disney’s classic live-action, family fantasy films, The Love Bug was released in a downtime for visual effects. It was the twilight of the studio system, as most studios were in the process of selling their backlots, auctioning off their assets, and closing their production departments. There were rare exceptions, notably Albert Whitlock’s matte-painting department at Universal. But it was Disney Studio having won its enduring fame with cartoon animation that maintained the tradition of a backlot and soundstages and in-house effects departments for live-action films.

In this Love Bug scene we see Herbie, the magical Volkswagen, in front of an old San Francisco firehouse overlooking the bay. Although painter Alan Maley visited San Francisco for research, this and other scenes were created in Burbank on the Disney lot. It is a city of the imagination, with a fanciful firehouse on a street that doesn’t exist, created with a bit of soundstage set and Maley’s masterful glass painting.

Matte painter Harrison Ellenshaw commented on this unsung example of matte-painting magic: “I wish I could have been there to watch Alan work on this painting. Very few matte artists would be so daring and clever. The composition is brilliant the idea of putting the telephone pole in the foreground helps balance the shot, and it’s a nice touch adding the two traffic cones. But when we watch the film we look past the foreground to see Herbie in front of this wonderful old firehouse, which is what the shot is all about.

“Note how Alan even incorporated some lens distortion into his painting the horizontals and verticals near the edges curve slightly, which is a subtle yet effective touch. We know it’s late in the day because of the long shadows, another daring and clever idea. Alan did this painting a few years before I joined the department as an apprentice, but I recall him telling me, years later, that he’d started the painting to match the live-action plate as if it were shot in bright sunlight. But since the set was inside a soundstage with stage lighting, he decided, after much struggling, to try it as if the live action were in shadow. Alan was very proud of this shot and actually kept it intact, a rarity in those days when a finished painting on glass was scraped off so the glass could be used again.”