Matte Painting – Sudden Impact

Matte World Digital © 2002

“The invading army was the technical people who built the machines. At first we [artists] were all confused traditional matte painting and digital was a head-on collision. There was lots of carnage. Then, eventually, the smoke cleared and it became clear what to do. What happened was artists who were afraid of the thing eventually said, ‘Step aside, let me take a look at that.'”

Robert Stromberg, digital matte painter

Although computer-generated effects had begun appearing in the 1980s, notably with ILM’s “Genesis Effect” of a barren planet becoming transformed into a garden world for Star Trek II, it was not until a decade later that digital technology became reliable and cost effective. The turning point was ILM’s creation of the realistic computer-generated dinosaurs for the 1993 release Jurassic Park.

Predictions of the time, which prophesied the end of all traditional visual effects, were greatly exaggerated. Makeup, creature costumes, animatronic effects, miniatures, and scale models all remain vital crafts, although every one of those disciplines has been changed by computer technology.

But the computer did have a sudden impact on other aspects of the craft. Almost overnight, optical printers were replaced because of the new freedom to scan images into a computer and seamlessly create final composites free of image degradation. And traditional matte painting was soon transformed, with digital paint programs allowing for new freedoms and, potentially, more complex shots.

But for the new breed of digital matte painter, the transition from brush and oils and canvas to software and computer monitors has not altered the irreducible essence at the heart of any creative equation the inventive mind and talent of the individual artist.

When director James Cameron was making this film about the doomed 1912 maiden voyage of the Titanic, the production logistics included a nearly full-scale re-creation of the luxury ship and a special studio, built in the Mexican seaside town of Rosarito, that included an eight-acre water tank and three large stages. The production’s scale, and the price tag that went with it, had Hollywood and movie critics primed for the kind of legendary box-office failure that bankrupts studios. What Cameron delivered was the most successful box-office film of all time, with eleven Oscars awarded at the Academy’s annual ceremony.

While the effects-heavy film took full advantage of digital technology, this climactic image of the crew of the Carpathia searching the icy waters for survivors was a fusion of traditional and digital techniques. The shot, created by Matte World Digital, combined a live plate of lifeboats shot in Mexico, physical and computer-generated models of floating icebergs, and a live-action smoke element added to the painted smokestack of the Carpathia. The rescue ship itself was created by Chris Evans as an old-fashioned, acrylic-on-Masonite board painting. The painting was then photographed and scanned into the computer along with the other elements, including a digitally painted dawn sky, in the final composite image.

The Carpathia painting marked a full circle for Evans, the first artist to take a matte painting into the digital realm (created at Industrial Light + Magic for a scene of a stained-glass knight magically coming to life in the 1985 release Young Sherlock Holmes). Although Matte World Digital had originally considered doing the ship with computer graphics, the looming deadline allowed only two weeks for the creating all the elements and a final composite. It was Evans who suggested it would be quicker to create the ship as a traditional matte painting, a rare recourse to brush and paints in the digital age.

For Evans, the Titanic assignment had a personal echo. His great-grandfather, John Bartholomew, worked for the White Star Line as chief victuals officer and was scheduled to sail on the Titanic maiden voyage as a company VIP. The night before the launch, however, Bartholomew was stricken with an illness and canceled his trip. The notice came so late his luggage was already aboard the ship, and early reports on the disaster listed Bartholomew as one of the casualties. “When he heard that the Titanic went down with so many of the friends he’d worked with for thirty or forty years, he was heartbroken,” Evans recalled in a December 1997 Cinefex special issue on the making of Titanic.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

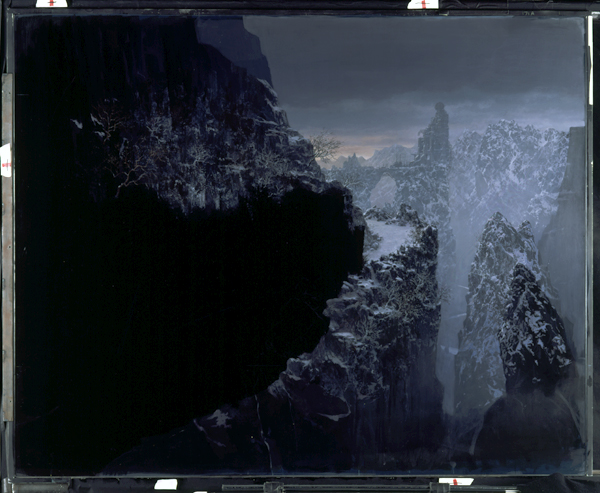

The 1990s was an intriguing decade for matte painting, a time when new digital tools appeared and began to be applied, but also a time when entire productions still embraced traditional effects. One such was Bram Stoker’s Dracula, with director Francis Ford Coppola contracting Matte World specifically to create matte shots the old-fashioned way. The film, set in the Victorian times that coincided with the earliest days of movies, inspired Coppola to attempt to use effects appropriate to that era. (Matte World did, however, dissuade the director from shooting glass shots on location, which, although a seminal effect, had always been laborious and time-consuming even under the best conditions.)

In this shot of a horse-driven carriage approaching Dracula’s castle, the live-action matte element was combined with artist Bill Mather’s painting on the same strip of film, with the camera rewound to film each new element. The film was then put into a high-speed camera to shoot several passes of “snow,” actually baking soda shaken through a wire mesh screen.

This shot also demonstrates the subliminal effects that can be achieved by a matte painting. Beginning with a production sketch by artist Jim Steranko, Matte World concept artist Sean Joyce worked with the director to develop the initial idea of the vampire’s castle being shaped like a body on a throne. “Francis wanted this subconscious effect of a tortured man, screaming some kind of plea to Heaven,” Joyce noted.

Casino (1995)

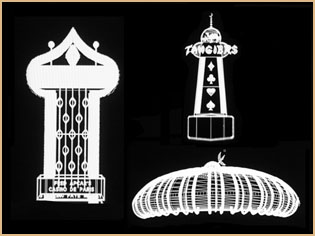

This Martin Scorsese film was set in the Las Vegas of 1974, a time period when the fabled Strip was dominated by the Tropicana and Flamingo hotels and such iconic structures as the glittering, 180-foot-tall Dunes sign. But twenty years later, when Scorsese was making Casino, those landmarks had been demolished. Enter Matte World Digital, the traditional matte-painting company having adapted to the new digital verities in both name and technology. Scorsese’s assignment was that the effects house re-create the Strip’s period look and add the fictitious Tangiers Hotel to the mix.

For the shot pictured here, Matte World Digital combined a live-action plate with computer-generated images of the Dunes sign and the Tangiers Hotel, with the glittering neon itself created through radiosity lighting software developed by Lightscape, a Silicon Valley firm. Prior to radiosity, the rendering of a 3-D computer model only accounted for light coming from a specific source, ignoring the way light actually interacts and breaks up. The complex interplay of direct illumination and “bounce light” is the way the real world looks, which is why the earliest computer-generated models with only direct light sources look so flat and unrealistic.

Using the 3-D wireframe models that Matte World Digital built in the computer, the radiosity software allowed for the computer-generated surfaces to incorporate a 2-D “mesh,” made up of triangles and rectangles, which helped to automatically determine and represent all illuminative gradations, from strong light sources to diffuse bounce-light effects. The Tangiers sign here is composed of some 158,000 mesh elements, the Dunes sign a staggering 2.5 million.